Introduction:

In a world so heavily guided by rules of society and rules of identity, it can be a constant struggle to find your place of comfort while also conforming to the boxes you’re expected to fit yourself into. Growing up in the United States, more specifically California, I’ve noticed an ever-growing conversation on the elements of one’s self and how that can serve to better them or hinder them in their journey of life. Over the past few years of my life, this conversation has led me to discuss my own gender identity, sexuality, and mental health. But another aspect, which seemed beyond my full control or understanding, was racial identity. I am Faye Vavra, and I am half white and half Japanese, making me biracial. That never seemed confusing or unique to me until I reached high school and college, and I realized there was so much weight put on one’s racial presentation in the adult world. Being a part of Generation Z I’ve seen the term “wasian” gain popularity within recent years as a way to identify those who are part white and part Asian, so that’s usually how I refer to myself now. But whatever someone may choose to call me as, beit wasian, hapa, Eurasian, biracial, halfie, or simply just “mixed,” it all boils down to one inescapable fact: I hold within me two genetic racial components that make up who I am. I can never be fully white, and I can never be fully Asian. However, that fact has never been difficult for me to accept, and that’s for one reason, which is that I look like I am Asian. I have tanned skin, straight dark hair (when it hasn’t been bleached and dyed outrageous bright colors), ethnic enough features, and dark brown eyes. I carry a strong likeness to my mother, who is fully Japanese, which is additional confirmation that I hold with me a direct connection to an Asian lineage. I even had the classic bangs and a bob haircut that every little Asian girl must endure as a rite of passage into your adolescence.

Eileen and Faye Vavra, August 2007

However, being mixed but still presenting clearly as a person of color does not personally ignorant to the experiences of those with the same genetic composition as me who have been labeled as “white passing.” Throughout history the concept of presenting as white passing has varied from being a blessing to a curse. In the end, though, the experiences are dictated by what group or community it is you are trying to belong to. Those who feel as though they are too white to belong to the Asian side of their culture may detrimentally suffer from being white passing, whereas those who want nothing more than to thrive in a world dominated by white privilege may happily take their place as a white passing individual. To imagine a life as someone who appears to be more white than Asian is to change the entire lens I see myself through, and I desperately wanted to know the answers to questions I had been asking myself for years. How does being a mixed Asian and white individual affect your life culturally, socially, professionally, and internally? Is there something universal we can all latch onto, or is your takeaway exclusively and uniquely based on the way you control your life, or the way your life controls you? Additionally, is there some sort of solidarity found in those who are biracial that differs from the experiences of those who are 100% Asian and 100% white? Through a number of various research methods, I set out to collect answers to these questions, and educate myself and whoever may read this on the ways in which one’s level of visually presenting whiteness can join or combat their Asian-ness in order to shape their life and identity today.

IN THE WORLD OF FAMILY CULTURE AND HERITAGE:

One of the most prominent aspects of one’s life that allows them to feel connected to their heritage or familial community is often the presence and acceptance of culture. Culture can exist within the realms of geographical locations, common interests, factors of personal identity, and of course, race. To connect with your ethnic culture is what can make or break the way one might connect with their friends and family and even their own sense of self. Within the wasian community this sense of connection has the opportunity to branch between both the Asian side and the white side. Unfortunately, this situation can also often find people split between two places at once. On one hand, the possibility of a dual perspective is opened up that is different from those who aren't biracial, and life can be “life richer and more inclusive,” (Marston). On the other hand, you also lack that full understanding and genetic devotion to one half of yourself, and one may find themself “struggling for acceptance by one side or another of their roots,” (Marston).

The mixed Odanaka cousins and Nicole (far left), December 2008

As a major element of my research I created an online survey displaying a variety of questions regarding the experiences of wasian individuals. I sent it out to friends, family, and peers in order to get responses from all mixed white/Asian people with varying Asian ethnicities, ages, and genders. Within the data of this survey I concluded that when it comes to being wasian, confusion can usually be found on the Asian side when it comes to cultural acceptance. I found that if given the opportunity to become 100% white or the opportunity to become 100% Asian, no one wanted to be fully white. However, only 75% of people said they would not choose to become fully Asian. Additionally, in studies published by Oxford University Press analyzing statistics from the US Census it was found that those who identify more as white felt a stronger sense of cultural isolation than those who identified as biracial or Asian (Xie & Goyette). Perhaps it is the cultural weight that can come with being Asian or being a person of color, and how that will oftentimes be much more consuming than the cultural weight of being white. To take pride in your white culture is to take pride in that which has already been accepted, but to take pride in your Asian culture is to undo a long history of discrimination and misinformation against it. To be white passing, then, can feel as though you lack the necessary parts to accept yourself into your cultural Asian community. How you look, white passing or not, can have an immense influence over how you categorize yourself. The question “what are you?” as familiarly mentioned in an NBC article written by Celeste Katz Marston is often asked of mixed or ethnically ambiguous peoples. We as mixed people often find this question frustrating because it means we aren’t seen as humans, we’re seen as unknown entities lacking place and purpose. As Marston said, this ambiguity can push you to get “used to checking the box for ‘other’ on forms,” almost casting aside your cultural identity as a point of importance and ignoring the struggle to identify yourself culturally based on how you look (Marston).

Hypothetically, if you had the choice to be genetically 100% white, would you take it?

Hypothetically, if you had the choice to be genetically 100% Asian, would you take it?

When asked in my survey if there was anything they felt like they’ve missed out on due to being biracial, nearly 40% of people responded saying that not learning the native language of the Asian side of their family was one of those important missing pieces. Within her personal narrative article detailing her experiences as a half Chinese half white person, author Anne Liu Kellor found herself also desiring this cultural connection to language as she reached college and strove to, as she said: “...reclaim my mother tongue of Chinese,” (Kellor). Speaking a native language, and other cultural practices, allow us to connect with family who are alive today and family who may have lived decades before us. Kellor writes that it was a cultural shift to living in China that allowed her to undo the pressure of whiteness that had been pushed on her as a child (Kellor). Both Kellor and those responding in my survey found that it was this whiteness that kept them from being able to fully dive into this other side of their cultural identity, and for that it brings a better understanding as to why the notion of “excessive whiteness” or being white passing can serve more as a hindrance than a benefit within the culture department. Similarly, it was proven through the research conducted utilizing US Census data that “first generation children are significantly more likely to be identified as Asian than third-generation children," meaning that the more removed by generations someone is from their immigrant Asian relatives the more likely they are to identify with the white side of their family than the Asian side due to a lack of direct cultural connection (Xie & Goyette).

But on the other hand, it doesn’t all have to be bad. With the dual identity that comes with being biracial you gain a cultural identity that most people do not have. The opportunity to embrace multiple cultures and inherit their values is something that can make someone more open-minded and diverse in their understanding of the world. Regardless of how you may present yourself or how you may appear to others racially, one who is biracial cannot deny the fact that personally connecting to multiple cultures is a unique and valuable experience those who are 100% white or 100% Asian might not ever get.

IN THE WORLD OF SOCIAL GROUPS AND THE PUBLIC EYE:

To exist as someone who is biracial in the social world is often to exist as a half-successful chameleon. You can camouflage yourself into both worlds, but oftentimes it feels as though it’s not enough. Within my survey over 90% of people said yes to the question: “Have you ever felt like you weren't "white enough" or weren't "Asian enough?" Personally, I grew up in a predominantly white area in California. There weren’t many Asian students at my school, and anyone who was Asian seemed to be a part of a very tight knit Filipino community I was not related to. However, I never felt like I had been missing out on some sort of social “Asian experience,” and thus I never took it upon myself to reach out and form my own community full of other Asian kids my age. But I will say, moments to share small bits of my own culture were often minimized due to having mostly white friends. It wasn’t until I moved to the Bay Area that I realized just how much a lack of social diversity had affected my upbringing and social standing. I wasn’t truly white to my white friends, but I hadn’t lived the same social and cultural life as other Asians, so I didn’t feel like I could truly relate to them either.

Faye Vavra (far right) and her high school friends, June 2018

How the public eye casts its gaze upon you can often shape how you gaze upon yourself, as we as humans are so prone to the judgment of others. Within the recent years of the Covid-19 pandemic, hate and discrimination towards the Asian population in the world has risen exponentially. The number of hate crimes against Asians in America has risen 339% in the past year, which brings with it a feeling of fear for those who will be deemed Asian enough by those passing you on the street or interacting with you in public (Yam). The features on your face, the color of your skin, and the choices you make to present yourself can be empowering, but can also be a point of attack made by cruel individuals. In Pew Research Center’s data collected on the experiences of multiracial individuals they found that “multiracial adults who are perceived as white are less likely to have experienced discrimination,” (Parker, et al). Regardless of your genetic composition, it can be seen through this fact that those who are wasian with a more white-leaning racial profile will be treated with a different kind of social respect than those who are more Asian-leaning. This benefit that comes with being white passing can then change the ways in which someone values or devalues themselves and their identity. Those who perhaps appear more Asian than other biracials might come to feel an element of resentment or pain due to their racial identity becoming a point of ridicule. To fight through a sea of racism in order to feel proud of who you are is to face a world not known by white passing and fully white people. But that is not to say those who are wasian and white passing feel completely relieved to avoid public discrimination. To pass on the street as a person of privilege holds with it a great responsibility. Those who are more white passing can find it difficult to accept themselves as Asian because they are removed from these social elements of being Asian in America today. With a more Asian-presenting life you must accept the sources of discrimination and exclusion from a world of white privilege, but you must also take pride in the diversity seen not only in your genetics, but also in the mirror. With a more white-presenting life you may resent your Asian side because you cannot fully experience the hardships of being a person of color in America, but you must also take pride in the generosity of privilege and how you can still connect with your heritage regardless of how the social world sees you.

IN THE WORLD OF PROFESSIONALISM AND CAREER:

Asians are often described as the “model minority” in the eyes of Americans. Stereotypically, we are seen as the math nerds, the computer geniuses, and the sterile intelligence machines. While statistically we may find ourselves advantaged, as Asian Americans are more likely to find educational and career-based success than any other ethnicity in America, that does not rule out the fact that your life’s trajectory is oftentimes assumed due to your race (Harris). However, does the influence of white genetics in addition to the Asian ones push that trajectory one way or another?

In an ideal world our success in our professional education and careers would be solely based on how hard we work and how much passion we have for that work. However, it is often the case that external factors will influence someone’s decisions when regarding another person with professional esteem. Interestingly enough, the experiences of those who are wasian in the professional world appear to mostly lean towards the neutral to positive end of influence rather than the negative end. Within my administered survey, not a single person said that their racial identity had a negative effect on their professional life, only a neutral or positive effect. Additionally, this statement is further proved through data collected at Pew Research Center as those who were mixed white and Asian were over two times as likely to find their racial background to be an advantage to them compared to any other mixed race group (Parker, et al). However, this is not to say that both the white and Asian identities had equal control in that statistic.

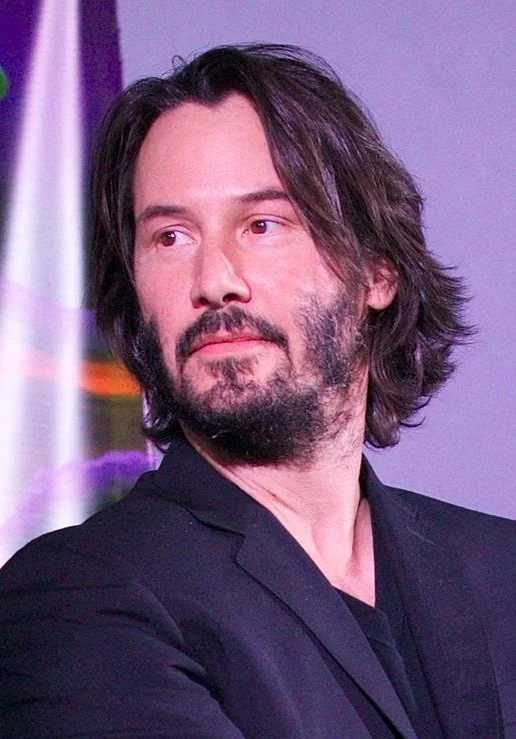

Keanu Reeves, 2013

While Asians might experience advantages due to their stereotyped probability of academic and technical success, it is still a prevalent fact that white privilege riddles every corner of America. To hold with you the label of “white” is to unlock many doors not open to people of color. Built on a world of white privilege, it only makes sense that this country will often favor those fair in skin or Eurocentric in their features. One of the most widely seen and influential job fields that experiences this is the entertainment industry. Asian Americans have been long left out of the media and entertainment world, as easily seen by a lack of positivity in my survey to the question: “Do you feel well-represented in the media today?” To be Asian and be in movies, TV shows, or behind the scenes is to portray a very specific narrative or role. It is rare to see someone who is Asian acting in America whose race is not a key trait of their character or story. While it is important to show the world the intimate and personal aspects of Asian cultures, it is rather disappointing to be so defined by your race that you cannot simply be seen as “human.” Few exceptions have existed throughout the years, and when observing the outliers one can often trace it to the presence of white privilege or type-cast fame. The most prominent and educational example of this phenomenon being: Keanu Reeves.

The star of hit movies such as The Matrix, Speed, the John Wick movies, and Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, Keanu Reeves is well revered not just within the pool of Asian actors in Hollywood, but in Hollywood as a whole. These roles also harbor little to no tie into his racial identity, and are exclusively based in colorless scripting. One might even be surprised to find out that in addition to being of European descent, Keanu Reeves is also Chinese. To break out of decades worth of Asian stereotypes seen in film and television and create such a name for yourself is inspiring, however it is impossible to ignore the presence of white privilege in this man’s life. Megan C. Hills writes excellently about this exact situation in an article centering around the actor. In her words, she truthfully says: “Like Reeves, I have a white-sounding surname to put on my CV and I’ve managed to break into spaces where minorities are heavily underrepresented,” (Hills). While the Asian community is able to rejoice in such an unproblematic and inoffensive source of representation through Keanu Reeves, we must also take to heart the lesson that can be learned from white privilege.

CONCLUSION:

Throughout years of experience as a biracial Asian, the story often leads people to find a sense of balance between their dual identities. Those who are wasian are more likely than any other biracial combination to embrace their racial identity as a way to embrace new cultures and ideas, and serve as a bridge between ethnic communities (Parker, et al). We have been gifted with a life that ties us into two very different cultures, and while it can oftentimes be a struggle to juggle such contrasting worlds, it can also be beautiful to understand the intricacies of the human experience through two lenses. Sometimes the ways we are raised and treated growing up can heavily influence our feelings towards ourselves and the world around us. For those feeling as though they cannot ever be “white enough” or “Asian enough,” it all comes down to what you feel is missing in your life and how you choose to fill that gap. For me personally, I felt I had not embraced my Japanese culture as much as I could have growing up, and took it upon myself to explore new foods, history, art, and media that made me feel more connected to who I truly was. Anne Kellor writes that reaching out and taking the time to hear the voices of others with similar experiences to you or the identity you wish to hold is how one can “open pathways to new conversations,” (Kellor). Just by conducting this research I have noticed myself learning stories and words coming from a like minded group I had not known before writing this paper. We as wasians may be a part of two different ethnic communities, but we are also a part of our own unique population that deserves just as much pride and representation as any other. This idea of intersectionality is worth bringing to the table, because it allows us to see the full picture of our identity and the ways in which overlaps between being white and being Asian affect us and complete us. Perhaps, if you are wasian like me, allowing yourself to embrace that part yourself can help you too.

The Odanaka family, April 2003

Annotated Bibliography

Harris, Keshia L. “Biracial American Colorism: Passing for White.” American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 62, no. 14, 2018, pp. 2072–2086., doi:10.1177/0002764218810747.

This article separates the experiences of biracial individuals and their influences of “white passing by ethnicity, the categories being African American, Latino Americans, Asian Americans and Native Americans. As my findings focus solely on the experiences of mixed Asian Americans, I limited my research to that section of this paper. Author Keshia L. Harris writes about the likelihood of mixed Asian Americans to identify more with their white heritage or their Asian heritage, and how these experiences compare to those of other mixed races. These statistics are influenced by various factors such as socioeconomic status, native spoken language, parental identity, or cultural practices. According to Harris these factors influence whether or not someone who is mixed will further their identity as leaning towards white or Asian, and whether or not that influences their place in society. This article stands as an important source of information detailing the more specific elements of mixed identity not discussed in other sources I’ve found.

Hills, Megan C. “What Keanu Reeves Taught Me about White-Passing Privilege.” Evening Standard, Evening Standard, 5 Sept. 2020, www.standard.co.uk/insider/celebrity/keanu-reeves-chinesehawaiian-asian-heritage-white-passing-a4539726.html.

Author Megan C. Hills writes in this article about how the concept of white passing privilege can influence one’s image in the public eye through the example of renowned Hollywood actor Keanu Reeves. Keanu Reeves is mixed Asian + Pacific Islander and white, and is rarely portrayed within typical Hollywood Asian stereotypes due to his white passing privilege. Hills writes about how Reeves’ representation of Asians in the media stands as a point of pride for other Asians, but also stands as a point of understanding that he was able to achieve more than other mixed Asians because he does not immediately read as Asian visually. This article excellently tackles the idea of how white privilege can affect those who might not even identify as white, and how those with the same racial background can have completely different experiences in life simply due to their face or presentation. Personally I find this writing useful not only for the commentary on white passing privilege, but also as an example of how it has affected people in America directly.

Kellor, Anne Liu. “Shapeshifting: Discovering the ‘We’ in Mixed-Race Experiences.” YES! Magazine, 9 Aug. 2021, www.yesmagazine.org/opinion/2021/08/09/mixed-race-experience-identity.

In this online journalism article author Annie Liu Kellor discusses her personal experiences and general take on the identity and life of a mixed race white and Asian person. From the perspective of someone who is middle-aged and has years of knowledge internally and externally exploring the idea of racial identity, this article allows for Kellor to make points of wisdom that speak to a more universal issue. This article specifically provides information not only in the personal narrative, but also a sense of social relevance as Kellor discusses how society has forced her to embark on her own personally dictated self-discovery as the implications of race in the bigger world had forced her to pick one or the other when identifying her race. While not containing factual support, this article provides a great sense of belonging and first-person experience that can support themes of belonging needed in the biracial community. Between the two identities of a white American and an Asian American, regardless of how you present yourself this article details the struggle to aspire for a sense of national belonging within your whiteness and cultural belonging within your Asian-ness.

Marston, Celeste Katz. “'What Are You?' How Multiracial Americans Respond and How It's Changing.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/whatare-you-how-multiracial-americans-respond-how-it-s-n1255166.

I was drawn by the title “What Are You?” for this article and knew I needed to include it as research, because that question resonates with so many mixed people of color. This article tackles mixed identity, even specifically Asian, as a sort of PSA into the lives of those struggling with their mixed identities. It brings in references to personal narrative, historical context, pop culture context, as well as compelling words to analyze all of the above. Personally, I took the personal and general experiences to heart, and was able to take from this a consensus of how these more nation-wide factors play into the individual experience.

Parker, Kim, et al. “The Multiracial Experience.” Pew Research Center's Social & Demographic Trends Project, Pew Research Center, 30 May 2020, www.pewresearch.org/socialtrends/2015/06/11/chapter-4-the-multiracial-experience/.

This article published by Pew Research Center showcases a number of valuable statistics and data surrounding the experiences and presence of biracial peoples. Ranging from the general % of biracial people in America to how they feel about their own racial identity, this article gives a lot of insight into quantitative factual information as opposed to qualitative personal information. Important points to take away from this research can be found in how biracial people are treated in society, and how they navigate through their lives, families, and selves. This research is also split up by ethnicity within the umbrella term of “biracial,” which allows readers to analyze specific subsections into the mixed race experience. Having raw data on these topics allows simple yet effective evidence to support more emotional and narrative claims.

Yam, Kimmy. “Anti-Asian Hate Crimes Increased 339 Percent Nationwide Last Year, Report Says.” NBCNews.com, NBCUniversal News Group, 14 Feb. 2022, www.nbcnews.com/news/asianamerica/anti-asian-hate-crimes-increased-339-percent-nationwide-last-year-repo-rcna14282.

This article provided me with accurate information and statistics regarding the recent events of anti-Asian hate in America. By providing numbers and facts, you can bolster an emotional argument and provide necessary shock in order to emphasize the importance of an event or situation. This article not only gave me that information, but also provided context and elaboration to help me understand the given data.

Yu Xie, and Kimberly Goyette. “The Racial Identification of Biracial Children with One Asian Parent: Evidence from the 1990 Census.” Social Forces, vol. 76, no. 2, Oxford University Press, 1997, pp.547–70, https://doi.org/10.2307/2580724.

The writing within this article not only furthers research and insight into the personal perspectives of Asian biracial individuals, but also sets historical and social context for those experiences. Additionally, this article stands out because it is taken from a different time period than the present. Having a generous amount of information from a generation ago allows one to compare and contrast the varying experiences of the past versus the present, and see what has or has not changed for biracial individuals. This article also takes data from the US 1990 Census, which allows for an extremely accurate and detailed nation-wide analysis of the biracial population. This includes the specific heritages of biracial individuals, as well as the percentages and origins of their families.